Line calendars were far more common. The calendar companies employed salesmen, paid on commission, who traveled the countryside visiting small businesses as well as vendor stalls at the local mercado. The salesmen brought with them a large selection of images from which customers could choose; the line calendars weren't brand specific, so didn't have a company's products painted into the artwork. Once the customer chose an image, the calendar would be sent to be printed with the customer's business name, address, and phone number. These custom printed calendars were then delivered to the business person in early December.

The business owners and mercado vendors would then give out these calendars to customers as a way to thank them for their business, as well as for promotional purposes; they were a year-long advertisement hanging right in the customer's home. The families' favorite calendar would often be displayed in the living room, with others in the kitchen and other parts of the house. Often the families enjoyed the images so much that they simply cut off the date pad and saved the calendar art, to be hung permanently in the family home.

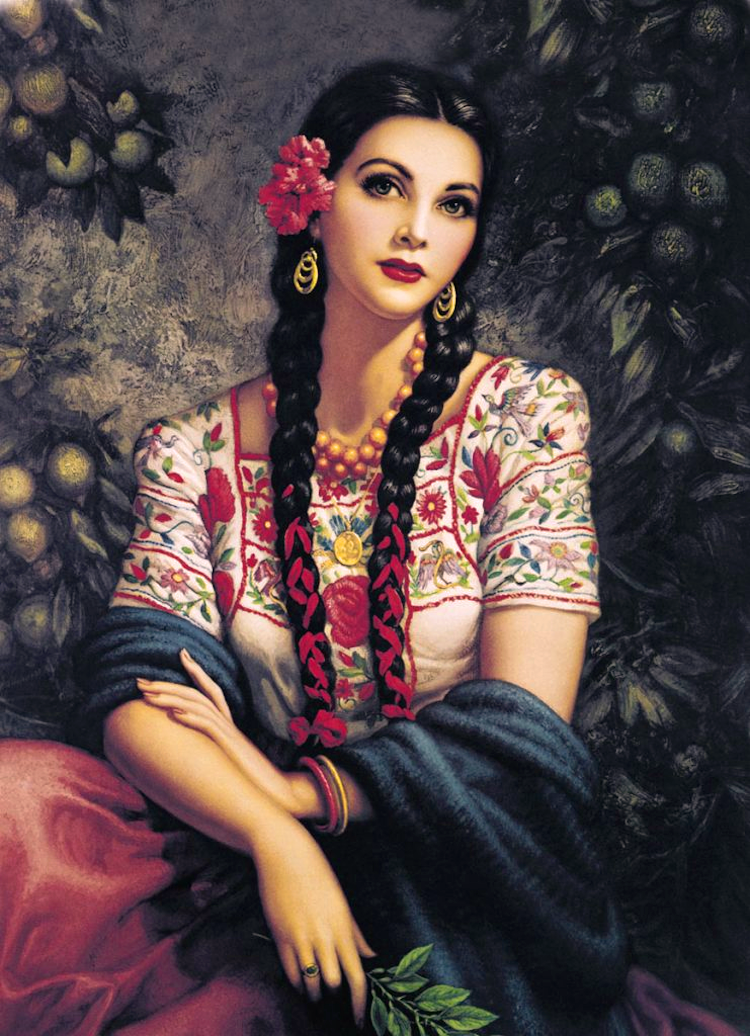

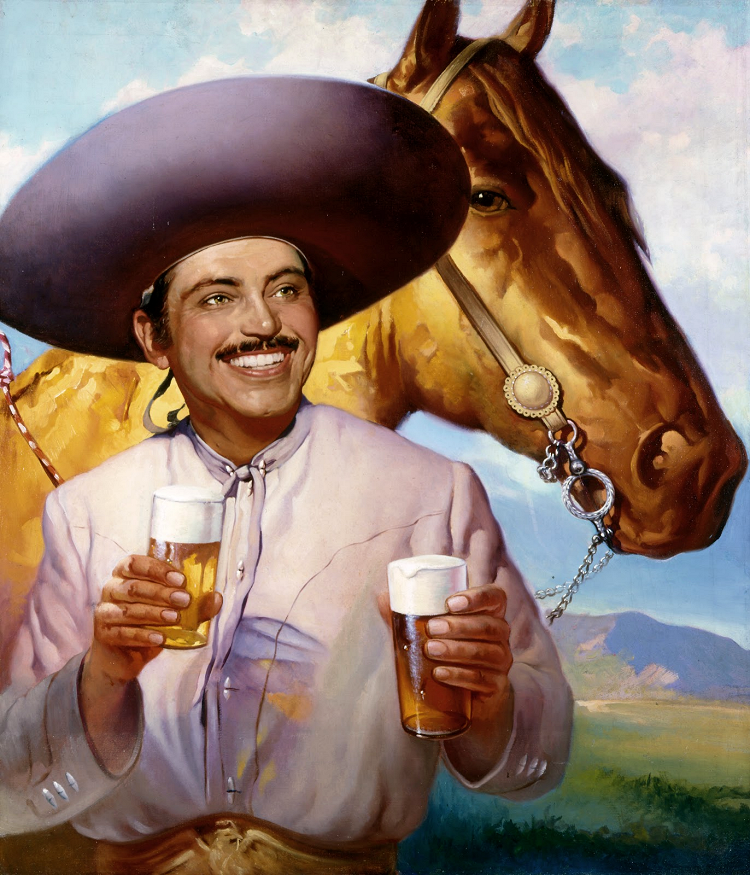

Many artists were employed creating the paintings reproduced in these calendars, some of the best-known being Antonio Gomez, Armando Drechsler, Jaime Sadurni, Eduardo Cataño, José Bribiesca Ruvalcaba, and Jesús Helguera. (Helguera is, by far, the most represented artist in this collection of images.) The subject matter reflected the Mexican government's push toward nationalism during that period, encouraging an artistic celebration of the country's own rich history and culture, freed from European and American influences. Aztec mythology, life in the village or on the rancho, women in regional costume, scenes of religious devotion were the sort of subjects featured in these brightly colorful images.

In spite of this commercial celebration of mejicanismo - happening at the same time as the post-Mexican Revolution artistic flowering that witnessed the work of the great painter/muralists, the surrealists, Frida Kahlo, and others - the calendar artwork also served to reinforce the racism and colorism inherent in the contemporary Mexican culture. Though usually dressed in traditional costume, most of the figures who people these scenes display conspicuously European features. This is especially evident in those that are female, who are usually portrayed as light-complected, fully made-up, and with "pin-up girl" physiques. While placed in settings and situations that mirror the indigenismo of the aforementioned fine artists, they instead have had almost all physical traces of ethnicity removed; the indio is celebrated in this work but rarely actually seen.

*

Full disclosure: When I lived in LA - 1986-1993 - I was a complete Hispanic/Latino wannabe. Nearly all my friends were Mexican-American, Mexican, or Central American. And they warmly included me in their friend and family circles, folded me in, made me feel a part of it all. Invited me to dinners, parties, clubs, family gatherings, weddings. They probably thought I was ridiculous - because I was - but I think they somehow appreciated this big güero's fascination with their lives and culture - both contemporary and traditional - and were always completely welcoming, encouraging, and incredibly kind. All this to say that, flaunting my fraudulent mejicanismo, I had - and actually wore - two t-shirts emblazoned with these last two Helguera paintings.

Sublime!

ReplyDeleteI too loved my Mexican community in San Francisco and finally for the last 20 years have lived in Mexico and not moving back to the states ever. I speak Spanish but am REALLY white yet it is fine with my family of friends here in Ajijic, Jalisco.

ReplyDeleteWonderful. In my experience, the Mexican people are just so kind, so welcoming. (If only we were that way to them....) I have a Facebook friend who is moving to Mexico - near Lake Chapala - even as I write this. And bravo to that! : )

DeleteAgain a lovely and well documented post about an obscure less know art, Gracias!

ReplyDeleteLike painted scenes from the peliculas of the Mexican cinemas Golden Age. Tito Guizar, Dolores del Rio, Lupita Tovar, Rasaura Revueltas, Juan Orol, Pedro Infante, Maria Felix and Manuel Palacios come to mind -Rj

ReplyDeleteJesus Helguera art is fantastic!!!!

ReplyDeleteCalendarios de reflexiones positivas, los colores representan la visión del artista sober la vitalidad de la cultura y el espíritu de México y su gente.

ReplyDeleteIdealizaciones de la vida en México y su fundamento más importante, la familia.

🇲🇽