|

| After 'Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe' by Manet - acrylic on panel - 30x40 - 2021. |

I'm very excited - if it's a mid-week post, I must be excited - to announce the opening of the most recent exhibition of my work. This brand new body of work, shown under the title Re:Pose - Subverting the Gendered Gaze in the Historical Nude, will be showing at Froelick Gallery, here in Portland, from 19 October to 27 November. Most of these paintings were begun, and all of them completed, during the odd and restricting months of the pandemic, and their subject matter attempts to confront some of the accepted ideals and assumptions inherent in the depiction of the nude figure in the history of Western painting. To further explain my various motivations related to this work, I've included my artist statement - concocting these things is obligatory, you know - at the end of this post.

|

| After 'Étude académique d'un torse masculin' by Ingres - acrylic on panel - 24x20 - 2020. |

|

| After 'La Chemise rose' by de Lempicka - acrylic on panel - 20x16 - 2020. |

|

| After 'The Venus of Urbino' by Titian - acrylic on panel - 24x36 - 2021. |

|

| After 'Bacchus' by Caravaggio - acrylic on panel - 8x8 - 2021. |

|

| After 'Nu devant la cheminée' by Balthus - acrylic on panel - 24x24 - 2020. |

|

| After 'Psyché abandonnée' by David - acrylic on panel - 16x12 - 2020. |

|

| After 'The Rokeby Venus' by Velázquez - acrylic on panel - 18x24 - 2020. |

|

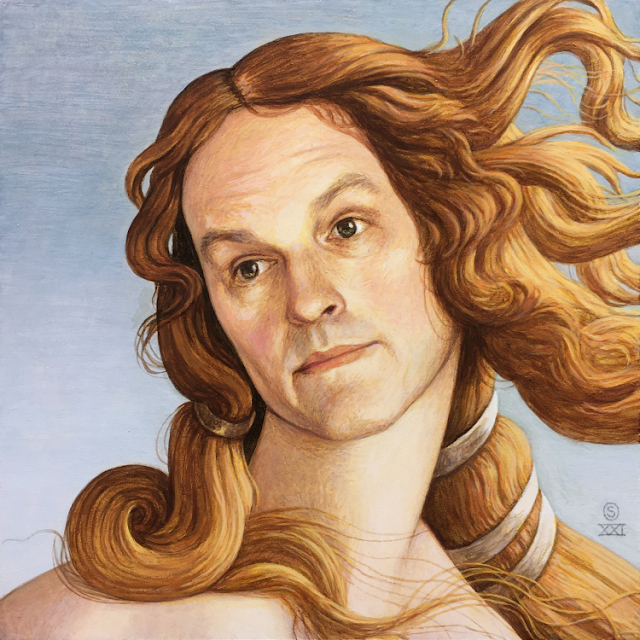

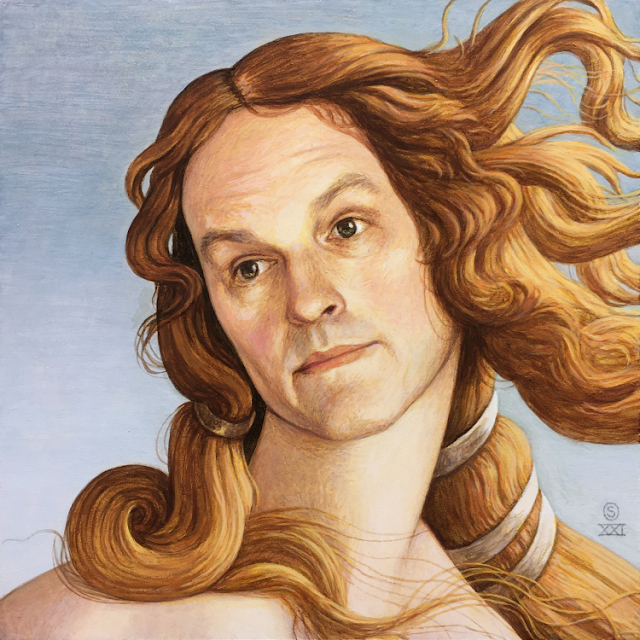

| After 'The Birth of Venus' by Botticelli - acrylic on panel - 6x6 - 2021. |

|

| After 'Portrait of a Lady' by Paris Bordone - acrylic on panel - 10x8 - 2020. |

|

| After 'Morte di Cleopatra' by Artemisia Gentileschi - acrylic on panel - 12x16 - 2020. |

|

| After 'Venus With a Mirror' by Titian - acrylic on panel - 24x20 - 2021. |

|

| After 'Le Mort de Marat' by David - acrylic on panel - 8x8 - 2021. |

|

| After 'Descanso de Marte' by Velázquez - acrylic on panel - 24x12 - 2021. |

*

Artist Statement

Re:Pose - Subverting the Gendered Gaze in the Historical Nude

Working on this body of work has been a wonderful challenge on several levels. The basic idea – taking a well-known nude from the history of Western art and transposing a male body for the original female – is something I’ve explored only fully twice in the past. I felt the results of those endeavors were successful and I’ve long planned to continue that exploration.

The question of who gets objectified in art, whose body is held up as beautiful, and who gets to decide this, is at the heart of this work. Historically, in Western art, at least since the Renaissance, the nude female body has always been portrayed as the ultimate of beauty, the ultimate object of desire. Endless tales have been told pictorially using the naked female form, the stories often stressing their sexuality, be it purity or amorality. And in the vast majority of these paintings the woman is a passive object. And in nearly all of them the artist was a man. It was the male gaze informing the female body.

At least until the last quarter of the twentieth century, the male nude was almost never – openly – presented as an object of beauty and desire. The male body was pictured as physically strong and aggressively active. Generally speaking – as long as we overlook all those passively sinuous, bound-up St. Sebastians and their ilk – images of male nudity were predominantly created by heterosexual male artists to be seen by a heterosexual male audience. Art was made by men, for men. So the question was, what would men want to see? The written history of the world is a history of the patriarchy, so why would we expect the history of art to be any different? Men ruled the world, men made the art, the history of art is a history of the male gaze.

So, simply, this work is a reversal of all that. How do we view a male body when it is presented in exactly the way we’ve always seen the female body presented? When the male body is passive? Coy, alluring, or merely vulnerable? In our present day, when society’s expectation of how men present themselves is in flux, when many men are directly challenging gendered norms of appearance and behavior, is the blatant objectification of the male body – the same objectification that has always been the lot of the female in Western art – an aberration or a necessary and healthy balancing?

But in this larger group I wanted to move the challenge outward, beyond just that question, challenging myself and perhaps the viewer as well. Western art is – pretty much by definition – made up almost entirely of pictures of white people. So I wanted to at least make some small challenge to that by placing people of color in the same compositions previously reserved for Caucasians. One of the models in several of the pieces – he has featured in previous work as well – is biracial, of Vietnamese heritage. I hoped to speak to a second issue with this model: the stereotype of the “unsexy” Asian male. The sexuality of the Asian man is so frequently played as a joke. Having two biracial nephews, the offensiveness of this is something I’ve certainly been made more aware of. Putting this model’s face and body in place of the objectified, sexualized female I hope is something of an answer to that, a rebuttal, putting the lie to that racist stereotype.

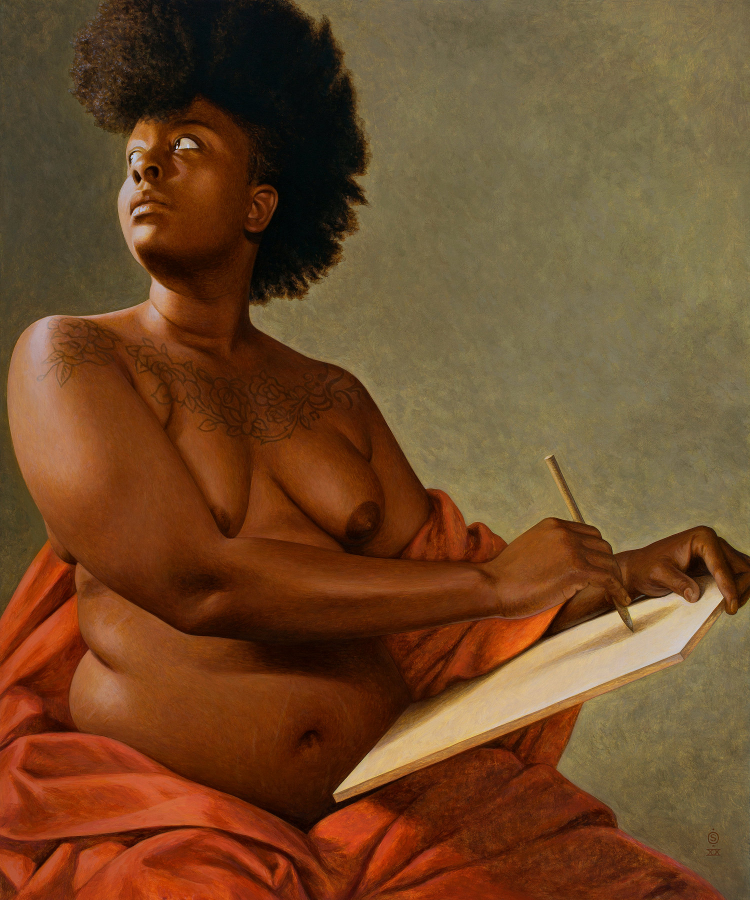

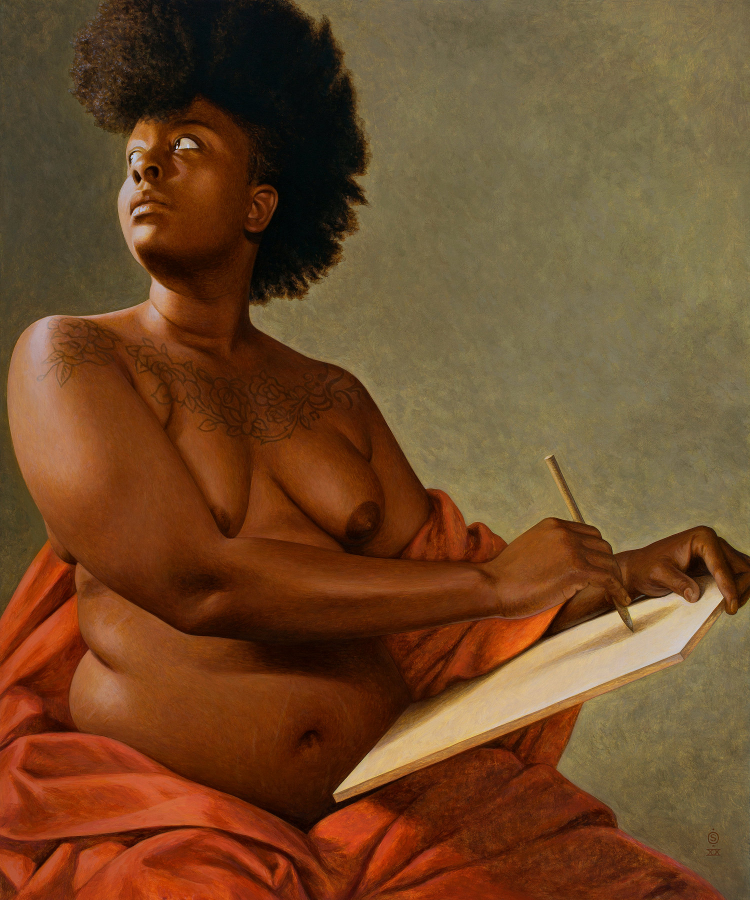

I was also thrilled that an African American woman agreed to pose for me. For the aforementioned reasons related to “whiteness,” and because I’ve only painted a person of African American heritage once or twice before. But also because this is the first time I’ve painted the female nude. The same model features in three paintings in this group. I wanted the chance to go in the opposite direction as I’d gone with the paintings of men: to take a painting of a nude man and replace the body with that of a woman. Finding original paintings to work from was more difficult than I’d imagined it would be. I wanted to create strong images of women, with nothing passive or concerned with prettiness, nothing that pandered to the viewer in an objectified or sexualized manner. But when I would put the female body into the same exact decidedly un-provocative pose as the male, the women’s body came off as passively alluring rather than powerful. It was kind of shocking. Is our cultural conditioning, the constant objectification and sexualization of the female body, so ingrained that it’s difficult for us to view it any other way? Thankfully, I eventually found paintings to work from that could support the feeling of strength I was going for.

There have been technical challenges as well. Using a nearly identical format as the earlier works I’ve chosen, these paintings have become a sort of collaboration between the original artist and myself. So I’ve had to carefully negotiate the differences in style – brushwork and the description of objects – existing between the two artists involved. Drapery has been a particular challenge. Earlier artists often painted drapery without a reference, so the folds of the fabrics are more suggested than realistic. But then I find when I try to copy those parts of the original, it only comes off as though – I – don’t know how to accurately paint drapery.

Another technical issue I’ve come across is the darkness of many of the paintings I’ve chosen as models. The particular acrylic technique I use makes it very challenging to calibrate just how dark is dark. It’s difficult to explain – basically, you put a dark over a dark, it appears to match, but when it dries it doesn’t – but it’s one of the reasons most of my work is fairly brightly lit. So I had to spend a lot of time adjusting the dark areas of the paintings. And this was also why the thought of achieving a smooth surface to the skin tones of my Asian and African American models was daunting. Skin tones of any color are very unforgiving; even the slightest deviation in color can signal a “problem” to the viewer. I was really relieved that it turned out to be easier than expected.

One last thing, a small thing certainly. But I was really happy to “steal” two of my paintings from women artists I’ve always admired, two very different artists and life stories: Artemisia Gentileschi and Tamara de Lempicka. The historical lot of women in the arts has been one of being disallowed, discouraged, ignored, and forgotten. So I hope this is one more tiny tweak to the nose of Western art.

|

| It was fun to adapt the big heap of food and clothing in the corner of Manet's famous composition, switching out the cast-off gown with a pile of men's clothes. |

|

| So, the right side of the collection is Manet's... (With a slightly "healthier" coloration.) |

|

| ... While the left side is mine. (The pretty little brooch replaces a big toad that Manet had put there. Of course I did; do I really seem like one to paint a toad...?!) |

Bravo on such interesting work!

ReplyDeleteThank you!

DeleteWow! Really like this collection!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much. It's been a really interesting experience for me; I learned so much doing these.

Delete