|

| Detail of the illustration for the month of Floréal. (Taken from a different printing than the other examples here.) |

The calendrier républicain français (French Republican calendar) was created and implemented during the French Revolution to celebrate the founding of the French Republic, and was designed in part to remove all religious and royalist influences from the calendar. It was part of a larger attempt at decimalization in France, with decimalization of the hours of the day, of currency, etc. The new system was used in government records in France and other areas under French rule, including Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Malta, and Italy.

Each day was now divided into ten hours - each hour into one hundred decimal minutes; thus an hour was one hundred and forty-four conventional minutes - but there were still twelve months, though each was now three weeks long, while each week consisted of ten days. The authorities having decided that the establishment of the French Republic in 1792 marked the beginning of a new era, the introduction of the new calendar on 22 September 1793 also heralded the beginning of Year II.

The republican calendar was used by the French government for about twelve years, from late 1793 until 1 January 1806/Year XIV, when it was finally abolished by Napoléon, already more than a year into his reign as empereur des Français. Decades later it was put into play once more, for eighteen days in May 1871/Year LXXIX, by the Paris Commune.

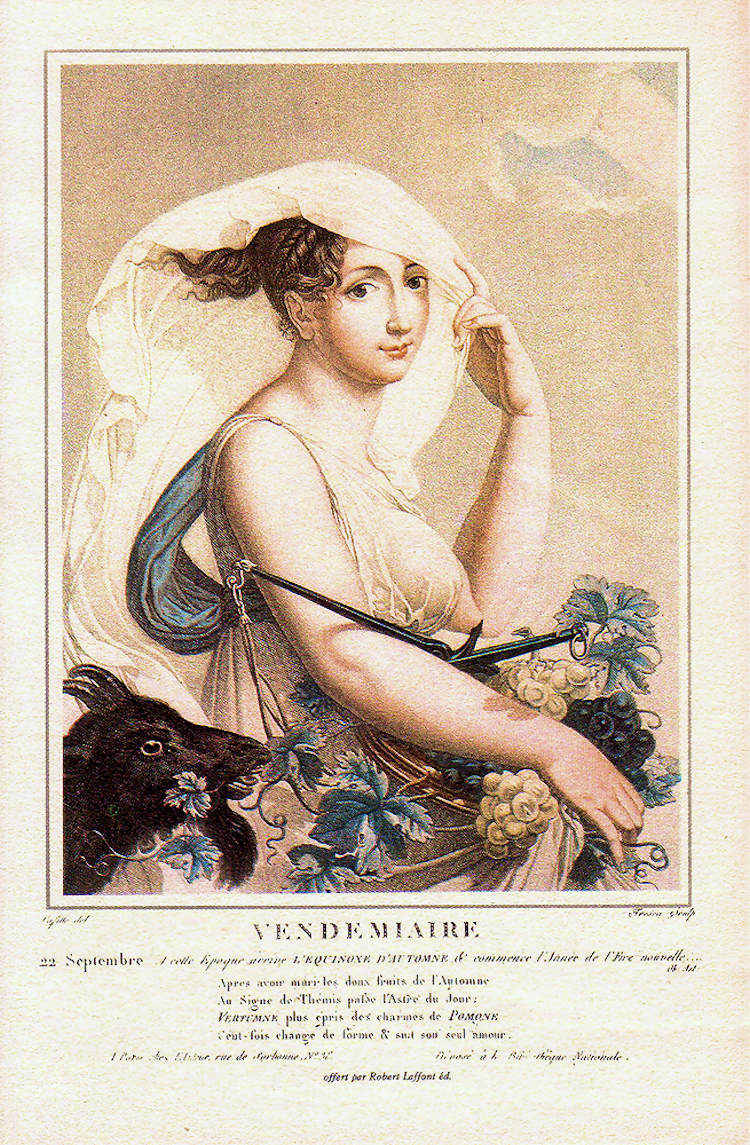

The following images are from an illustrated calendar of 1797-8, engraved by Salvatore Tresca after the originals of Louis Lafitte.

Autumn:

Vendémiaire (from French

vendange, derived from Latin

vindemia, "vintage"), starting 22, 23, or 24 September

Brumaire (from French

brume, "mist"), starting 22, 23, or 24 October

Frimaire (from French

frimas, "frost"), starting 21, 22, or 23 November

Winter:

Nivôse (from Latin nivosus, "snowy"), starting 21, 22, or 23 December

Pluviôse (from French pluvieux, derived from Latin pluvius, "rainy"), starting 20, 21, or 22 January

Ventôse (from French venteux, derived from Latin ventosus, "windy"), starting 19, 20, or 21 February

Spring:

Germinal (from French germination), starting 20 or 21 March

Floréal (from French fleur, derived from Latin flos, "flower"), starting 20 or 21 April

Prairial (from French prairie, "meadow"), starting 20 or 21 May

Summer:

Messidor (from Latin messis, "harvest"), starting 19 or 20 June

Thermidor (from Greek thermon, "summer heat"), starting 19 or 20 July (On many printed calendars of Year II (1793–94), the month of Thermidor was named Fervidor (from Latin fervidus, "burning hot"))

Fructidor (from Latin fructus, "fruit"), starting 18 or 19 August